5.9 Teste de Hipóteses

Seja um parâmetro \(\theta\) pertencente a um espaço paramétrico \(\Theta\), i.e., o conjunto de todos os possíveis valores de \(\theta\). Considere uma partição tal que \(\Theta_0 \cup \Theta_1 = \Theta\) e \(\Theta_0 \cap \Theta_1 = \emptyset\). Um teste de hipóteses é uma regra de decisão que permite decidir, à luz das informações disponíveis, se é mais verossímil admitir \(\theta \in \Theta_0\) ou \(\theta \in \Theta_1\).

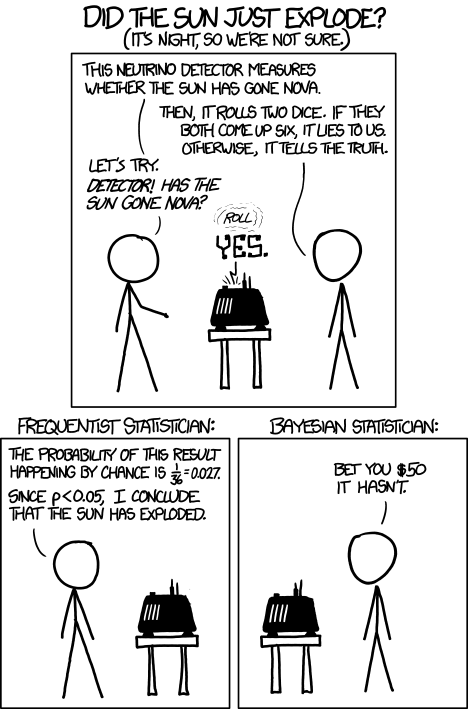

Figura 5.2: Did the sun just explode? de https://xkcd.com/1132/

Exercício 5.27 Veja

- Seção 3.4 de (Paulino, Turkman, and Murteira 2003).

- Capítulo 9 de (S. J. Press 2003).

Exercício 5.28 Verifique a hipótese de que a palavra ‘hipótese’ vem do grego hipo (fraca) + tese = ‘tese fraca’ conforme sugerido por Renato Janine Ribeiro no Provoca de 24/08/2021.

5.9.1 Fator de Bayes

In a 1935 paper and in his book Theory of Probability, Jeffreys developed a methodology for quantifying the evidence in favor of a scientific theory. The centerpiece was a number, now called the Bayes factor, which is the posterior odds of the null hypothesis when the prior probability on the null is one-half. (Kass and Raftery 1995, 773)

Suponha que deseja-se testar \(H_0: \theta \in \Theta_0\) vs \(H_1:\theta \in \Theta_1\). Do teorema de Bayes obtém-se

\[\begin{equation} P(H_i|D) = \frac{P(D|H_i)P(H_i)}{P(D|H_0)P(H_0) + P(D|H_1)P(H_1)} \tag{5.14} \end{equation}\]

Desta forma

\[\begin{equation} \frac{P(H_1|D)}{P(H_0|D)} = \frac{P(D|H_1)}{P(D|H_0)} \frac{P(H_1)}{P(H_0)} \nonumber \tag{5.15} \end{equation}\]

Aplicando \(P(H_0)=P(H_1)=1/2\) conforme (Jeffreys 1935) e (Jeffreys 1961), define-se o fator de Bayes por

\[\begin{equation} B_{10} = \frac{P(D|H_1)}{P(D|H_0)} \tag{5.16} \end{equation}\]

Conforme (Kass and Raftery 1995, 776), no caso mais simples, quando as duas hipóteses são distribuições únicas sem parâmetros livres (o caso do teste “simples versus simples”), \(B_{10}\) é a razão de verossimilhança. Em outros casos, quando há parâmetros desconhecidos sob uma ou ambas as hipóteses, o fator de Bayes ainda é dado por (5.14), mas as densidades \(P(D|H_0)\) e \(P(D|H_1)\) são obtidas integrando, e não maximizando sobre o espaço de parâmetros.

Podem-se considerar as referências sugeridas por (Kass and Raftery 1995, 777).

| \(2 \log_e B_{10}\) | \(B_{10}\) | Evidência contra \(H_0\) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 a 2 | 1 a 3 | Nem vale mencionar |

| 2 a 6 | 3 a 20 | Positiva |

| 6 a 10 | 20 a 150 | Forte |

| >10 | >150 | Muito forte |

5.9.1.1 Pacote BayesFactor

(Richard D. Morey and Rouder 2024) apresentam o pacote BayesFactor.

Exemplo 5.35 Podemos comparar as funções clássicas com BayesFactor::ttestBF(). De acordo com a documentação, “o fator de Bayes fornecido por ttestBF testa a hipótese nula de que a média (ou diferença média) de uma população normal é \(\mu_0\)”.

As hipóteses podem ser escritas da seguinte forma: \[\left\{ \begin{array}{l} H_0: y_i \sim N(\mu_0,\sigma^2) \\ H_1: y_i \sim N(\mu_1,\sigma^2) \\ \end{array} \right. \]

Conforme apontado por Richard D. Morey and Rouder (2011),409, Jeffreys (1961) sugere colocar prioris no tamanho do efeito padronizado (\(\delta=\mu/\sigma\)). Neste caso, \(y_i \sim N(\sigma\delta,\sigma^2)\). Os autores ainda indicam que “essa estrutura a priori é inspirada pelo conhecimento de que os tamanhos reais dos efeitos normalmente não são grandes, e que o analista é agnóstico quanto à direção de qualquer efeito possível”. Apontam ainda que a priori com distribuição Cauchy padrão para \(\delta\) “quantifica uma suposição de que parâmetros verdadeiros excessivamente grandes são muito menos plausíveis do que tamanhos de efeito pequenos, mas ainda são possíveis”.

A estrutura da priori para \(\delta\) é expressa da seguinte forma. \[\left\{ \begin{array}{l} H_0: \delta = 0\\ H_1: \delta \sim Cauchy(r) \\ \end{array} \right. \]

A priori não informativa imprópria (de Jeffreys) para \(\sigma^2\) é dada por

\[\begin{equation} \pi(\sigma^2) \propto \frac{1}{\sigma^2}. \tag{5.1} \end{equation}\]

A combinação destas prioris para \(\delta\) e \(\sigma^2\) é chamada priori de Jeffreys–Zellner–Siow (JZS).

| Parâmetro de escala | Valor de \(r\) |

|---|---|

| Medium (padrão) | \(\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\) |

| Wide | \(1\) (Cauchy padrão ou \(t_1\)) |

| Ultrawide | \(\sqrt{2}\) |

O fator de Bayes é calculado via quadratura gaussiana, para mais detalhes veja a Rouder et al. (2009), Richard D. Morey et al. (2011) e Richard D. Morey and Rouder (2011).

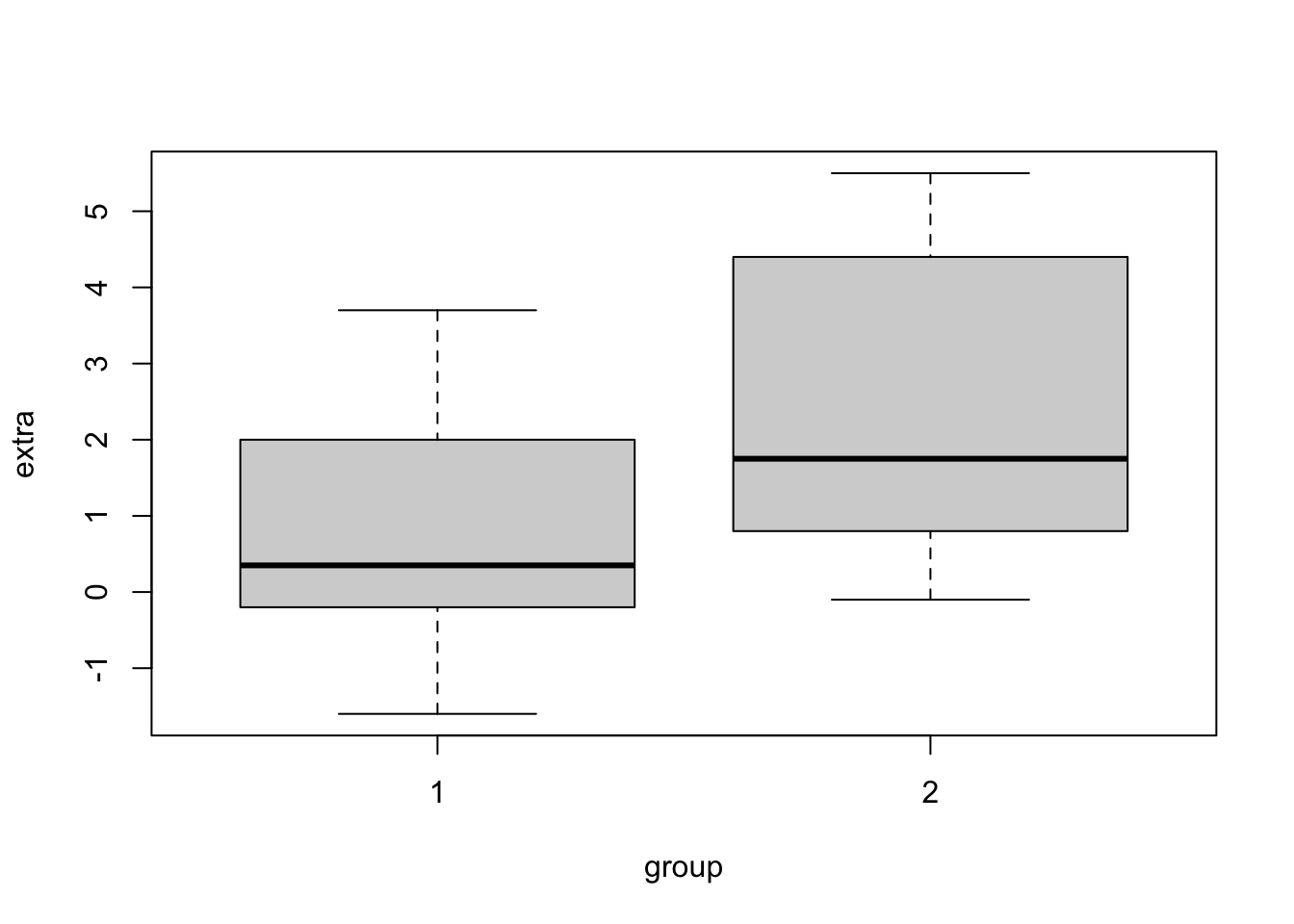

## classical paired t test

t.test(x = sleep2$extra[sleep2$group==1],

y = sleep2$extra[sleep2$group==2], paired = TRUE)##

## Paired t-test

##

## data: sleep2$extra[sleep2$group == 1] and sleep2$extra[sleep2$group == 2]

## t = -4.0621, df = 9, p-value = 0.002833

## alternative hypothesis: true mean difference is not equal to 0

## 95 percent confidence interval:

## -2.4598858 -0.7001142

## sample estimates:

## mean difference

## -1.58# classical Wilcoxon (signed rank test (median = 0 versus median > 0)

wilcox.test(x = sleep2$extra[sleep2$group==1],

y = sleep2$extra[sleep2$group==2], paired = TRUE)##

## Wilcoxon signed rank test with continuity correction

##

## data: sleep2$extra[sleep2$group == 1] and sleep2$extra[sleep2$group == 2]

## V = 0, p-value = 0.009091

## alternative hypothesis: true location shift is not equal to 0## bayesian paired t test

ttestBF(x = sleep2$extra[sleep2$group == 1],

y = sleep2$extra[sleep2$group == 2], paired = TRUE)## Bayes factor analysis

## --------------

## [1] Alt., r=0.707 : 17.25888 ±0%

##

## Against denominator:

## Null, mu = 0

## ---

## Bayes factor type: BFoneSample, JZSExemplo 5.36 Em Python.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import pandas as pd

from scipy.stats import ttest_rel, wilcoxon

from bayesfactor import ttestBF

# Carregando os dados do conjunto de dados sleep

sleep2 = pd.DataFrame({

'extra':[0.7,-1.6,-0.2,-1.2,-0.1,3.4,3.7,0.8,0.0,2.0,1.9,0.8,1.1,0.1,-0.1,4.4,5.5,1.6,4.6,3.4],

'group':[1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,1,2,2,2,2,2,2,2,2,2,2],

'ID':[1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]

})

# Gráfico de dispersão

plt.figure(figsize=(8, 6))

plt.scatter(sleep2['group'], sleep2['extra'])

plt.xlabel('Grupo', fontsize=12)

plt.ylabel('Diferença', fontsize=12)

plt.title('Diferença de horas de sono por grupo', fontsize=16)

plt.xticks([1, 2])

plt.show()

# Teste t pareado clássico

t_stat, p_value = ttest_rel(sleep2['extra'][sleep2['group'] == 1],

sleep2['extra'][sleep2['group'] == 2])

print(f"Teste t pareado clássico: t={t_stat:.4f},p={p_value:.4f}")

# Teste de Wilcoxon (teste de postos sinalizados) clássico

w_stat, p_value = wilcoxon(sleep2['extra'][sleep2['group'] == 1],

sleep2['extra'][sleep2['group'] == 2])

print(f"Teste de Wilcoxon clássico: w={w_stat:.4f},p={p_value:.4f}")

# Teste t pareado bayesiano

bf = ttestBF(x=sleep2['extra'][sleep2['group'] == 1],

y=sleep2['extra'][sleep2['group'] == 2], paired=True)

print(f"Fator de Bayes para o teste t pareado: {bf:.4f}")Exercício 5.29

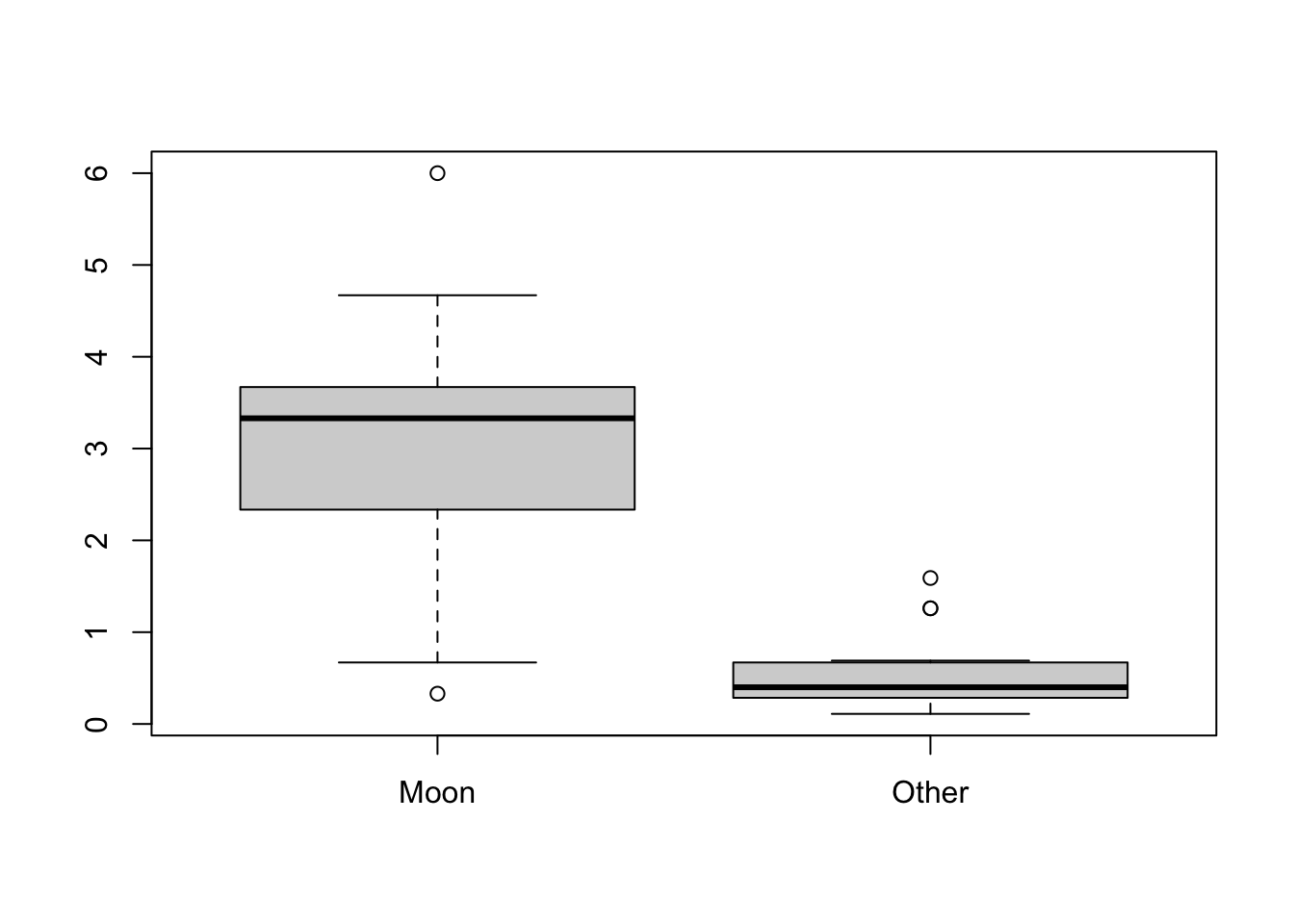

Exemplo 5.37 Exemplo Moon and Agression de (Moore and McCabe 1989, 410), que fornece o número de comportamentos agressivos de pacientes com demência durante duas fases do ciclo lunar (cheia e não-cheia). Cada linha corresponde a um participante.

# lendo dados

ma <- read.csv('https://filipezabala.com/data/moon-aggression.csv')

# gráfico

boxplot(ma)

##

## Paired t-test

##

## data: ma$Moon and ma$Other

## t = 6.4518, df = 14, p-value = 1.518e-05

## alternative hypothesis: true mean difference is not equal to 0

## 95 percent confidence interval:

## 1.623968 3.241365

## sample estimates:

## mean difference

## 2.432667# classical Wilcoxon signed rank test (median=0 versus median>0)

wilcox.test(x = ma$Moon,

y = ma$Other, paired = TRUE)##

## Wilcoxon signed rank exact test

##

## data: ma$Moon and ma$Other

## V = 119, p-value = 0.0001221

## alternative hypothesis: true location shift is not equal to 0## Bayes factor analysis

## --------------

## [1] Alt., r=0.707 : 1521.194 ±0%

##

## Against denominator:

## Null, mu = 0

## ---

## Bayes factor type: BFoneSample, JZSExemplo 5.38 Em Python.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import pandas as pd

from scipy.stats import ttest_rel, wilcoxon

from bayesfactor import ttestBF

# Lendo os dados

ma = pd.read_csv('https://filipezabala.com/data/moon-aggression.csv')

# Gráfico de boxplot

ma.boxplot()

plt.title('Agressividade na Lua vs Outros Dias')

plt.ylabel('Nível de Agressividade')

plt.show()

# Teste t pareado clássico

t_stat, p_value = ttest_rel(ma['Moon'], ma['Other'])

print(f"Teste t pareado clássico: t={t_stat:.4f},p={p_value:.4f}")

# Teste de Wilcoxon (teste de postos sinalizados) clássico

w_stat, p_value = wilcoxon(ma['Moon'], ma['Other'])

print(f"Teste de Wilcoxon clássico: w={w_stat:.4f},p={p_value:.4f}")

# Teste t pareado bayesiano

bf = ttestBF(x=ma['Moon'], y=ma['Other'], paired=True)

print(f"Fator de Bayes para o teste t pareado: {bf:.4f}")Exercício 5.31 Veja

- (Kass and Raftery 1995)

- Seção 3.4.1 de (Paulino, Turkman, and Murteira 2003)

- Seção 9.5.1 de (S. J. Press 2003)

- A vinheta de

BFpack(Mulder et al. 2021) em https://cran.r-project.org/package=BFpack.

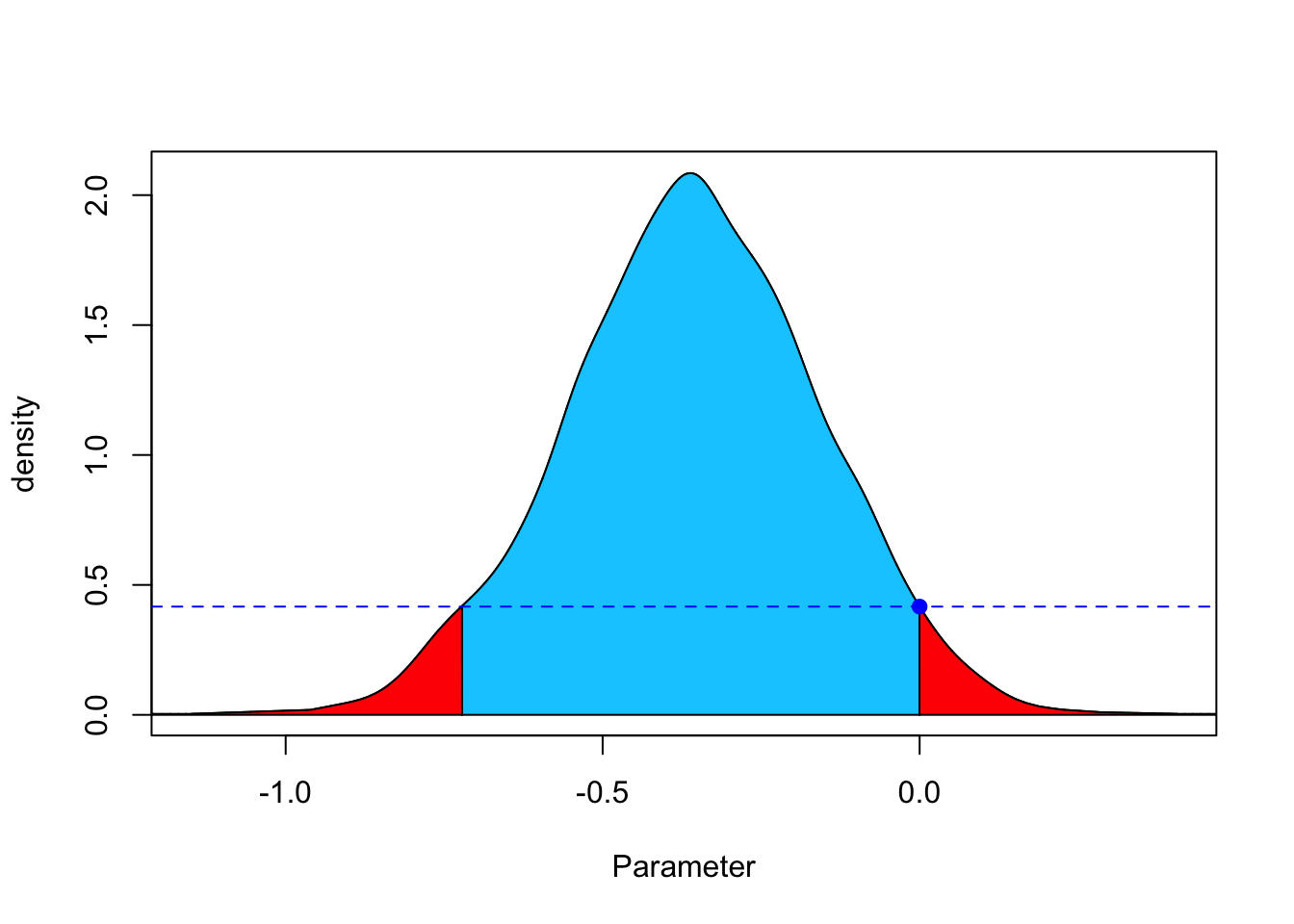

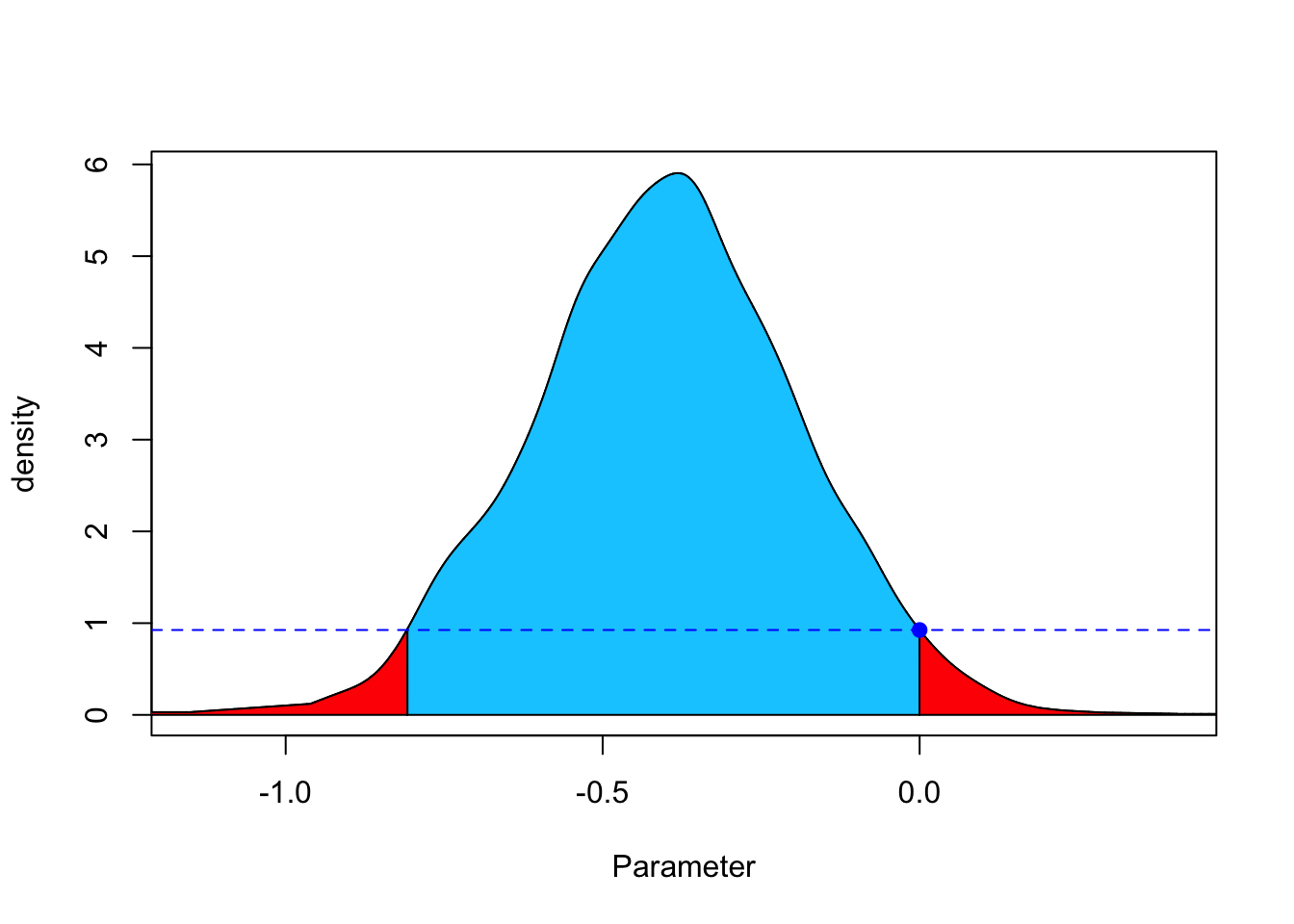

5.9.2 FBST

FBST é o acrônimo para Full Bayesian Significance Test, proposto por (Carlos Alberto de Bragança Pereira and Stern 1999) para testar hipóteses precisas (sharp hypotheses), amplamente revisado em (Carlos A. de Bragança Pereira et al. 2008) e (Carlos Alberto de B. Pereira and Stern 2020). Para idéias iniciais, veja o artigo de Eduardo E. R. Junior (2016-04-20).

5.9.2.1 Pacote fbst

Kelter (2022) apresenta fbst, um pacote R para o Full Bayesian Significance Test para testar uma hipótese nula precisa contra sua alternativa por meio do valor de evidência \(e\) conforme (Carlos Alberto de Bragança Pereira and Stern 1999).

# https://cran.r-project.org/package=fbst

library(fbst)

set.seed(57)

grp1 <- rnorm(50,0,1.5)

grp2 <- rnorm(50,0.8,3.2)

p <- as.vector(BayesFactor::ttestBF(x=grp1,y=grp2,

posterior = TRUE,

iterations = 3000,

rscale = "medium")[,4])

# flat reference function

res <- fbst(posteriorDensityDraws = p, nullHypothesisValue = 0,

dimensionTheta = 2, dimensionNullset = 1)

summary(res)## Full Bayesian Significance Test for testing a sharp hypothesis against its alternative:

## Reference function: Flat

## Hypothesis H_0:Parameter= 0 against its alternative H_1

## Bayesian e-value against H_0: 0.9265912

## Standardized e-value: 0.02228466

# medium Cauchy C(0,1) reference function

res_med <- fbst(posteriorDensityDraws = p, nullHypothesisValue = 0,

dimensionTheta = 2, dimensionNullset = 1, FUN = dcauchy,

par = list(location = 0, scale = sqrt(2)/2))

summary(res_med)## Full Bayesian Significance Test for testing a sharp hypothesis against its alternative:

## Reference function: User-defined

## Hypothesis H_0:Parameter= 0 against its alternative H_1

## Bayesian e-value against H_0: 0.9529035

## Standardized e-value: 0.01343346

5.9.3 Valores-p bayesiano

O valor-p preditivo a posteriori (Paulino, Turkman, and Murteira 2003) e a probabilidade de direção (Makowski et al. 2019) são reportados na literatura como ‘valores-p bayesianos’.

5.9.4 Combinando ferramentas

(Gannon, Pereira, and Polpo 2019) sugerem que “os pesquisadores não precisam abandonar completamente o valor p, o índice de significância mais conhecido, mas devem parar de usar níveis de significância que não dependem do tamanho da amostra”.

tab <- matrix(c(1,7, 4,4), nrow = 2, byrow = TRUE)

rownames(tab) <- c('C','T') # Controle/Tratamento

colnames(tab) <- c('+','-') # Respondeu positivamente/negativamente

(tab <- as.table(tab))## + -

## C 1 7

## T 4 4##

## Pearson's Chi-squared test

##

## data: tab

## X-squared = 2.6182, df = 1, p-value = 0.1056##

## Pearson's Chi-squared test with Yates' continuity correction

##

## data: tab

## X-squared = 1.1636, df = 1, p-value = 0.2807##

## Fisher's Exact Test for Count Data

##

## data: tab

## p-value = 0.2821

## alternative hypothesis: true odds ratio is not equal to 1

## 95 percent confidence interval:

## 0.002553456 2.416009239

## sample estimates:

## odds ratio

## 0.1624254# Fator de Bayes

fh <- function(x,y){

(choose(8,x)*choose(8,y))/(17*choose(16,x+y))

}

fa <- 1/81

bf <- function(x,y){

fh(x,y)/fa

}

BF <- matrix(nrow = 9, ncol = 9)

rownames(BF) <- paste0('x.',0:8)

colnames(BF) <- paste0('y.',0:8)

for(i in 0:8){

for(j in 0:8){

BF[i+1,j+1] <- bf(j,i)

}

}

addmargins(round(BF,3)) # note a questão do arredondamento## y.0 y.1 y.2 y.3 y.4 y.5 y.6 y.7 y.8 Sum

## x.0 4.765 2.382 1.112 0.476 0.183 0.061 0.017 0.003 0.000 8.999

## x.1 2.382 2.541 1.906 1.173 0.611 0.267 0.093 0.024 0.003 9.000

## x.2 1.112 1.906 2.052 1.710 1.166 0.653 0.290 0.093 0.017 8.999

## x.3 0.476 1.173 1.710 1.866 1.633 1.161 0.653 0.267 0.061 9.000

## x.4 0.183 0.611 1.166 1.633 1.814 1.633 1.166 0.611 0.183 9.000

## x.5 0.061 0.267 0.653 1.161 1.633 1.866 1.710 1.173 0.476 9.000

## x.6 0.017 0.093 0.290 0.653 1.166 1.710 2.052 1.906 1.112 8.999

## x.7 0.003 0.024 0.093 0.267 0.611 1.173 1.906 2.541 2.382 9.000

## x.8 0.000 0.003 0.017 0.061 0.183 0.476 1.112 2.382 4.765 8.999

## Sum 8.999 9.000 8.999 9.000 9.000 9.000 8.999 9.000 8.999 80.996## [1] 0.6108597## [1] 0.09228027Exemplo 5.39 Em Python.

import numpy as np

from scipy.stats import chi2_contingency, fisher_exact

from scipy.special import comb

# Criando a tabela de contingência

tab = np.array([[1, 7], [4, 4]])

# Teste qui-quadrado sem correção de Yates

chi2_stat, p_value, dof, expected = chi2_contingency(tab, correction=False)

print(f"Teste qui-quadrado sem correção: chi2={chi2_stat:.4f},p={p_value:.4f},dof={dof}")

# Teste qui-quadrado com correção de Yates

chi2_stat, p_value, dof, expected = chi2_contingency(tab, correction=True)

print(f"Teste qui-quadrado com correção: chi2={chi2_stat:.4f},p={p_value:.4f},dof={dof}")

# Teste exato de Fisher

odds_ratio, p_value = fisher_exact(tab)

print(f"Teste exato de Fisher: odds ratio={odds_ratio:.4f},p={p_value:.4f}")

# Fator de Bayes

def fh(x, y):

return (comb(8, x) * comb(8, y)) / (17 * comb(16, x + y))

fa = 1/81

def bf(x, y):

return fh(x, y) / fa

BF = np.zeros((9, 9))

for i in range(9):

for j in range(9):

BF[i, j] = bf(j, i)

# Adicionando margens à matriz BF (aproximado)

BF_with_margins = np.c_[BF, np.sum(BF, axis=1)]

BF_with_margins = np.r_[BF_with_margins,[np.sum(BF_with_margins,axis=0)]]

print("\nMatriz BF com margens (aproximada):")

print(np.round(BF_with_margins, 3))

# Calculando o BF observado

BF_obs = bf(1, 4)

print(f"\nBF observado: {BF_obs:.4f}")

# Calculando o p-value (aproximado)

p_value_bf = np.sum(BF[BF <= BF_obs]) / 81

print(f"P-value (aproximado): {p_value_bf:.4f}")5.9.5 Testes agnósticos

[A]gnostic tests, in which one can accept, reject or remain agnostic with respect to a given hypothesis. (Stern 2016, 1)

References

https://stats.stackexchange.com/questions/570605/understanding-the-jeffreys-zellner-siow-jzs-prior-in-bayesian-t-tests↩︎

https://pingouin-stats.org/build/html/generated/pingouin.bayesfactor_ttest.html#pingouin.bayesfactor_ttest↩︎

https://terrytao.wordpress.com/2024/08/02/what-are-the-odds-ii-the-venezuelan-presidential-election/↩︎